The fertile lands of Mesopotamia are rightly hailed as a “cradle of civilization”, where some of the most important human innovations originated, from agriculture and writing to religion and music. The Penn Museum in Philadelphia has long been home to one of the world’s most significant collections of ancient artifacts from the region – but for years, only a limited number of pieces were shown in encyclopedic, old-school displays that did not do them justice.

Now, after a $5m renovation lasting more than three years, the museum is reopening its Middle East galleries, having substantially expanded and completely reconceived them – with more than half of the nearly 1,200 objects on view to the public for the first time.

“This is one of the most important collections from the Middle East anywhere in the world,” said the Penn Museum director, Julian Siggers. “The material here is in every single art history textbook.”

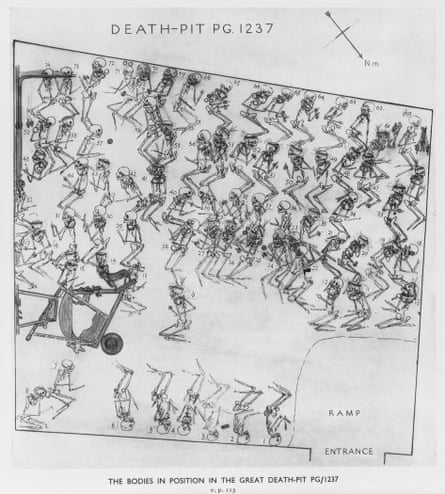

The centerpiece is the section on the Royal Cemetery at Ur, in what’s now southern Iraq, which Penn excavated in partnership with the British Museum from 1922 to 1934. Agatha Christie herself visited during the legendary expedition, which inspired her novel Murder in Mesopotamia. Dating to about 2,450BC, the site contained more than 2,000 Sumerian graves, of which 16 were determined to belong to royalty.

Little is known about the woman known as Queen Puabi, but her burial finery – a stunning gold headdress, elaborate jewelry and a “cloak” made of more than 50 strands of carnelian, lapis lazuli and agate beads – is so sumptuous that the dozens of alabaster vessels and bowls and jars made of precious metals that she was buried with utterly pale in comparison.

Other highlights of the Royal Cemetery are a lyre decorated with a huge bull’s head in gold, silver and shell mosaic that is one of the oldest known musical instruments and the famous Ram in the Thicket, one of a pair of exquisite gold and lapis lazuli statuettes, whose mate is at the British Museum. The sinister side of all of this wealth and finery was a “death pit”, where dozens of royal attendants were buried after being killed by blows to the head after the death of their master.

But the new permanent Middle East galleries are not just about riches and treasure – though there is plenty of it. Through artifacts both extraordinary and commonplace, the exhibits chart the course of human development in the Fertile Crescent over a period of almost 10,000 years, examining the transition to farming and sedentary life, along with numerous associated inventions.

“The first cities, the first writing, first irrigation, first metallurgy – all of these innovations which our own people have built on – start right here in this region, and here is the tangible evidence of that,” said Siggers.

The exhibits draw from Penn’s collection of more than 100,000 artifacts from the Middle East, the result of decades of research there. In 1889, the university sponsored an expedition to Nippur – the first American-led excavation in Mesopotamia – and it later went on to explore some 40 sites in what is now Iraq and Iran.

While the oldest items on display are charred seeds from about nine millennia ago that indicate early crop cultivation, the story really gets under way with a pottery jar, circa 5,400 to 5,000BC, that’s one of the world’s earliest known wine vessels.

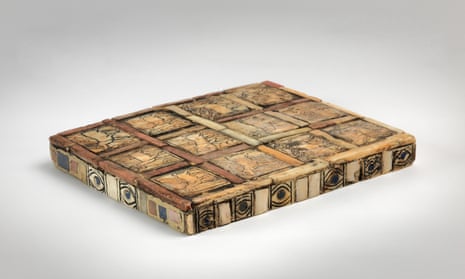

Sections on tools, illustrated seals and sacred objects show how, within another two millennia, the inhabitants of Mesopotamia had begun to organize their settlements into cities, with established political, economic and religious structures. By around 3,000BC, the Sumerians had developed cuneiform – first, pictographic symbols, and later, wedge-shaped markings.

“This is the moment when writing is invented,” said curator Holly Pittman. “This is a period when [people] visually describe a lot of the world that they live in. It’s a technology of knowledge. And it happens really fast.”

An array of cuneiform tablets demonstrate how the use of writing spread, first for trade and economic needs and later for religious and literary purposes. A “spreadsheet” from 1,400BC Nippur, for example, lists 3,000 cattle coming from other sites to be used for a plowing project, while a medical text describes recipes for poultices. Several pieces narrate parts of the epic of Gilgamesh, considered one of the world’s first literary works.

An animated projection simulates the experience of walking through Ur – at one point home to more than 20,000 people – showing merchants conducting business, the courtyard of the sacred moon god and a panoramic view from the roof of a temple.

The last 3,000 or so years are covered in less depth, but significant works include a monumental relief of a genie, circa 883 to 859BC, from the palace of Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II in Nimrud – a site the Islamic State largely destroyed in 2015. From the Islamic period come gorgeous tiles and ceramic dishes, mainly from Rayy, once a thriving city near modern-day Tehran until it was sacked by the Mongols in the early 13th century.

Some of the most evocative objects aren’t the elaborate jewelry or monuments to kings or gods but the mundane articles of daily life, such as a baby’s footprint lovingly preserved in clay nearly 4,000 years ago by a new parent, or the 3,750-year-old school tablet on which a student practiced the same cuneiform letter 360 times.

In the end, what’s most compelling about these rooms of ancient artifacts is the vast sweep of human history they narrate – and the commonalities it reveals between our lives today and those of people millennia before us.